“I am hurt all over, but I cannot tell the full extent yet, because the doctor is not done taking inventory. He will make out my manifest this evening. However, thus far he thinks only sixteen of my wounds are fatal. I don’t mind the others.”

Mark Twain, ”Niagara,” 1875.

Manifest entered English vernacular from either French or Italian influences. The meaning in old French was of something “evident” or “palpable,” and indeed it is that latter understanding which most accurately conveys the sensorial associations of the word. For something to “be manifest” implies its inhabitance in a space—not only physical presence, but the capability for physical apprehension. It is a thing in reach, a form which is open to touch. Its more distant Latin origin seems—at first—to make this clear. Here manifestus derives, in part, from manus, hand—an etymology familiar in words like manual, or manufacture. But the other half of the derivation has less of a consensus. If manifestus is taken to mean “caught by hand” (and “to make manifest,” consequently, taken to be “caught in the act”), then perhaps infestare—to attack, disturb, to “seize.”1 And there is something powerful this would offer to its history. The manifest was, after all, a document of violence.

A “manifest,” as Edward Hatton’s Merchant’s Magazine defined it, “is a Transcript of a Master of a Ship’s Cargo, showing what is due to him for Freight from each person to whom the Goods in his Ship belong.”2 With an economy of definitional deft, it embeds the manifest’s meaning within seventeenth-century notions of property and commerce. For a thing to appear in a manifest, it explains, it must be owned. That thing must have value. And so, through the shifting structures of global distribution, it carried out the violent ends of its dictates. In the pages of the manifest, resources could be stripped out of the world of nature and brought into a world of commerce. It deprived enslaved persons—at least for the readers of the document—of humanity and subjectivity. It may not have been the only tool necessary for carving up the geographies of indigenous lands, but it was the one responsible for recording the riches of their material cultures, preparing them for ships bound across the ocean and placing them in the storehouses of colonial encampments.

What’s more, contrary to its more manual etymology, the manifest had now become “transcribed”—no longer fixed in hand, but abstracted into the ink that marked its name on linen paper. And that, digitization aside, is where it has stayed, as a means for marking out relations: economic, legal, and otherwise. While for most of us it would be hard to say that this label brings to mind anything other than a more archaic, officious synonym for a listing of materials, its historic association with transportation (as in a ship’s “manifest,” or a plane’s “manifest”), still remains.

My personal history in manufacturing these sorts of listings goes back about a decade and a half, when I created the first prototype for what would become Sourcemap at MIT’s Center for Civic Media. The original idea was not to make a list. It was to make a map with a calculator. A map, because we were interested in being able to see where the parts of a product were coming from. And a calculator, because we were attempting to quantify the impact of those piecemeal geographies. Given that our primary interest as “makers” was in what we were producing, rather than what we had purchased, there was a palpable resonance in knowing how far our materials had traveled and how much they had cost—not as a final bill in dollars, but in social and environmental footprint at each stage of the process. It was not the case that we set out to create listings. After all, that’s what we were trying to move away from—from the stacks of Digikey catalogues that assembled components as placeless lines on pages, their perfect product numbers absent the unrepresentable textures which constitute the reality of human production. So when listings finally appeared, it was not that we had sought them out. It was rather that they seemed a necessary precondition of what (we supposed) were other, more interesting things.

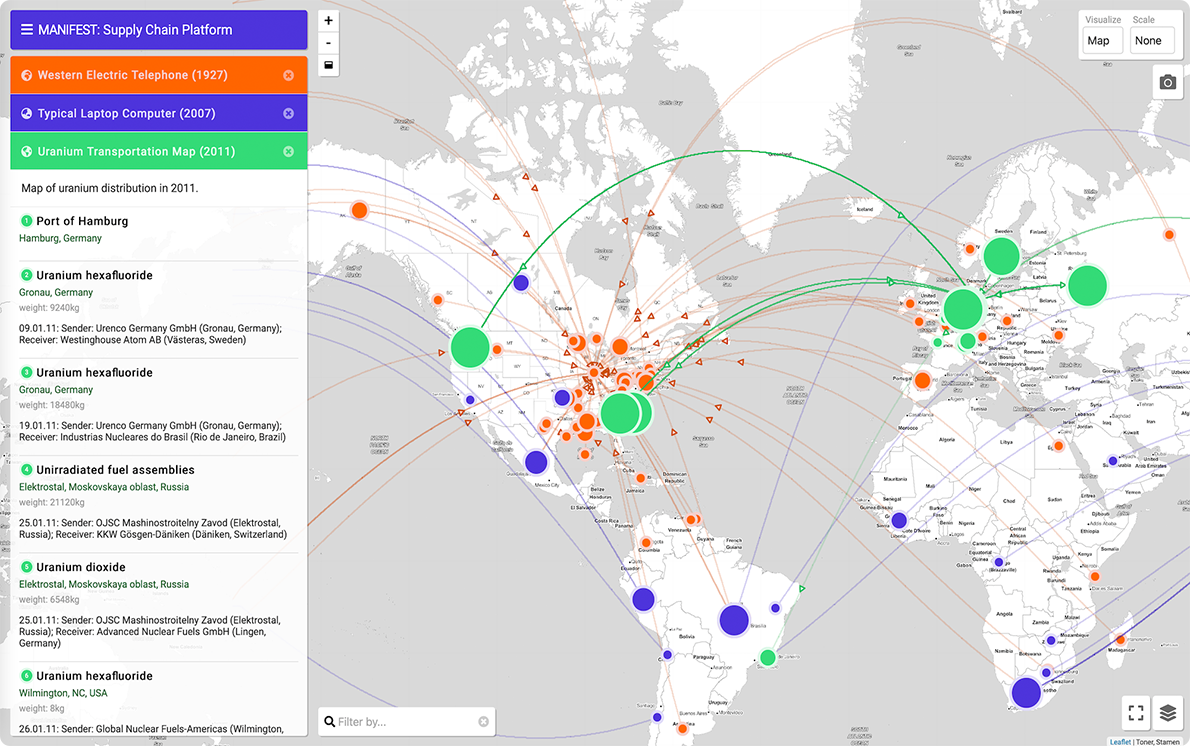

Manifest Screenshot (2021).

And in some ways this new project continues this work. Manifest is “an investigative toolkit intended for researchers, journalists, students, and scholars interested in visualizing, analyzing, and documenting supply chains, production lines, and trade networks.” Certainly the map is still present. But the calculator—although Manifest supports visualizing quantitative data—is less so. This is partly because while approximate information proved to be meaningful in geographic visualization, approximate calculations were not. Without access to enough accurate data the conclusions could be inaccurate, or worse—misleading. This is one of the reasons why Sourcemap has become (re)produced as a tool for business, rather than as the messy means of “muckraking” it was once, initially framed. Though woefully incomplete in their own way, corporate actors are the most likely to have detailed quantitative data, or at least the power to compel its collection.

Manifest diverges in a number of other, more meaningful, ways. It is less invested in centralizing supply chain data, and less interested in monolithic or comprehensive accounts of a supply chain. It provides a scaffolding for collecting fragments of networks at particular moments—particular pieces in particular places. These decisions attempt to acknowledge the power of listing, to work against the idea of making yet another tool most suited to those who have the power to not just take, but make, inventory. It rejects the collected and complete in favor of the distributed, the partial, and the temporary.

In so many ways, this project comes not because of, but in spite of my previous work in this area. I’ve spent a lot of the past decade thinking about the politics of supply chain transparency, especially since it has become such a frequent reference in the annals of corporate social responsibility (along with more pliable terms like “supply chain resilience”). The quickness of its colonization is a little surprising, but it was foreshadowed for me by the suggestion offered by one apparel industry executive, whose (here unnamed) firm had received a lot of negative press regarding their suppliers’ labor practice. They had enthusiastically agreed that total transparency in the supply chain would not just be tolerated, but welcome. With every worker under continuous surveillance, mapped and live-streamed direct to consumers, there would be no dark spaces left open to even the slightest possibility of unwanted exposure. Left unsaid was that if everything was seen to be available, then no one would ever want to look at it.

This is part of what had led me to resist this kind of politic as unsatisfying—not only an inevitably partial effort, but an increasingly passé one. It’s the same old story. From Upton Sinclair’s jungle to sweatshop summer, to workers jumping from factories and a global pandemic ripping through workers in warehouses and factories, we’ve always known that the world we’ve made depends on conditions we’d rather not think about, in places—with people—we never had. But we keep on living with it, more and more each year. Everybody knows. But they either miss the point, or don’t—can’t—care.

What brought me back is years of asking: what’s the alternative? I’ve never found a compelling one, at least in the immediate, practical sense. In returning to the idea of “supply chain transparency,” then, I want to do so not only with new tools, but with a new perspective. Ursula Le Guin once wrote that seeing the way things are doesn’t matter to most, but it does for some. And even those who, having seen the secret at the heart of their world, decide to go back to their lives must do so with the knowledge of the price that has been paid for them.

The supply chain, as a social model for production, is a failure. This is not to say that nothing wonderful has come from its time. The technologies that modern logistics made possible have saved lives, they have provided new forms of communication, produced a world that is more connected and aware of itself, one that is capable of new kinds of expression. But it has come at a terrible cost. How can the society they have structured be seen as any kind of success when so many have been exploited, displaced, or enslaved, with entire countries and cultures that have been mined, and with labor regimes founded on the extraction of value at any cost? Supply chains stand amid the greatest period of environmental degradation in the history of the world, of landscapes torn asunder, oceans and air polluted. They have tied the world into a shape that is both fragmented and fragile, and for every marvel at their end there are countless runs of almost useless, morally broken objects—dead on arrival, and destined for the dump.

In Twain’s words the manifest becomes an accounting of injuries. I think this provides a better model for unraveling the global supply chain than transparency. Rather than allow transparency to remain as a form of corporate responsibility, with “mapping the supply chain” an exercise in corporate power, “making out its manifest” might now attempt to account for our value, and our injuries. It records the places where labor has been exploited, where the earth has been plundered, where waste overruns into rivers, and poison bleeds into the air. It is not a proclamation from on high, but an admonition from below. Not an attempt at supply chain resilience, but an opportunity for supply chain reconciliation.